The Instrumentum Laboris [IL] should be abandoned as a guide for the Synod fathers in October!

Reports and commentary, from Rome and elsewhere, on the XIV Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops

DISQUISITIONS

…being thoughts on Synod 2015 from various observers

As a general rule, Letters from the Synod will not burden readers with lengthy texts. When a major text of exceptional thoughtfulness and importance comes our way, however, we’ll bring it, in full, to our readers’ attention.

Such is the case with Dr Douglas Farrow’s analysis of the Instrumentum Laboris, the “working document”, of Synod 2015, which we offer below. Professor Farrow’s detailed description of the numerous weaknesses of the Instrumentum Laboris will, we hope, be carefully studied by all those concerned with Synod 2015’s deliberations – including those who prepared the Instrumentum Laboris, the Synod fathers, and the experts invited to participate in the Synod’s official debates.

Douglas Farrow holds the Kennedy Smith Chair in Catholic Studies at Montréal’s McGill University. He is the author of several well-received theological studies (including Ascension Theology; Thirteen Theses on Marriage; and, most recently, Desiring a Better Country). Professor Farrow and his wife, Anna, are the parents of five children. XR2

Douglas Farrow holds the Kennedy Smith Chair in Catholic Studies at Montréal’s McGill University. He is the author of several well-received theological studies (including Ascension Theology; Thirteen Theses on Marriage; and, most recently, Desiring a Better Country). Professor Farrow and his wife, Anna, are the parents of five children. XR2

Twelve Fatal Flaws in the Instrumentum Laboris

The Instrumentum Laboris [IL] should be abandoned as a guide for the Synod fathers in October. Its flaws are legion, beginning with the fact that it is very badly organised; as intellectual architecture it fails completely, lacking both beauty and functionality. And though it claims to “serve as a dependable reflection of the insights and perceptions of the whole Church on the crucial subject of the family” (§147), in reality it undermines both the family and the Church itself, by legitimising a way of thinking that the Church has always regarded as illegitimate. In support of that claim I will enumerate just a few of its flaws.

1. The IL doesn’t seem to know what ‘the Gospel of the Family’ is.

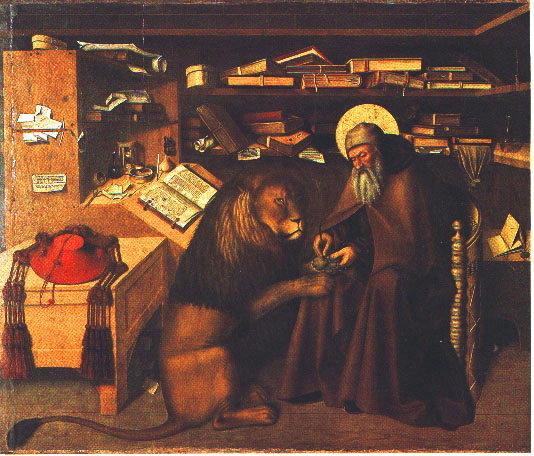

The IL tells us that the Church proclaims “untiringly and with profound conviction the ‘Gospel of the Family’, entrusted to her together with the revelation of God’s love in Jesus Christ and ceaselessly taught by the Fathers, the masters of spirituality, and the Church’s Magisterium” (§2). That gospel is said to span the history of the world “until it reaches, at the end of time, its fulfillment in the mystery of Christ’s Covenant, with the wedding of the Lamb” (§46).

One looks in vain, however, for a proper description of this gospel, which is more slogan than substantive announcement. The nearest thing to a definition appears at §4: “what revelation … tells us about the beauty, the role and the dignity of the family.” Unfortunately very little is said in elaboration of this. Even less is said about the relation between the gospel, the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and the “Gospel of the Family” or the issues facing the family. Already, in this vital respect, the IL fails as the working outline of an authentically ecclesial document.

2. The IL speaks of a crisis without making clear what that crisis is.

We are told that the reason the “Gospel of the Family” must be proclaimed afresh is that there is a pressing need to confront the situation in which the family finds itself today. That situation includes, inter alia, the turmoil produced by wars and persecution, together with “cultural, social, political and economic factors, such as the excessive importance given to market logic, that prevent authentic family life and lead to discrimination, poverty, exclusion, and violence” (§90). It also includes “a troubling individualism which deforms family bonds and ends up considering each component of the family as an isolated unit, leading, in some cases, to the idea that a person is formed according to his own desires, which are considered absolute” (§6). “Added to this is the crisis of faith, witnessed among a great many Catholics, which oftentimes underlies the crisis in marriage and the family” (ibid.; cf. §76).

Just as it is not quite clear what the “Gospel of the Family” is, however, it is not entirely clear what the main crisis is. The world has always known poverty and brutality and moral confusion, and it doesn’t need the Church to tell it that such evils exist. What is most noteworthy about the situation of the family today? What is the Church’s peculiar responsibility, precisely as steward of the gospel of Jesus Christ, in supporting and protecting the family? How, in particular, is the crisis of faith to be addressed? These questions, surely, are where deliberations ought to begin, but the IL neither begins with them nor arrives at them.

3. The IL sends conflicting signals about the proper starting point.

In calling rather vaguely for “a more through examination of human nature and culture” (§8), the IL does call also for a Christological analysis of human nature in its familial dimensions: the whole exercise, we are told, is to be conducted with “our gaze … fixed on Christ” (§4). But there is hardly any Christology at all in the document. The real starting point seems rather to be – and this is deeply ironic, given the lament about individualism – an existential one: “People need to be accepted in the concrete circumstances of life” and supported “in their searching” (§35). “The Church’s point of departure is the concrete situation of today’s families” (§68). If there is an “urgent need to embark on a new pastoral course,” that course must be “based on the present reality of weaknesses within the family“ (§106; cf. §81). “Pastoral work … needs to start with listening to people” (§136; cf. §83).

A more uncertain note could hardly be sounded. Which is it to be? Effective confrontation of the crisis facing the family by determined recourse to the Word of God, incarnate in Jesus Christ and proclaimed in Scripture and tradition? Or by listening, “free from prejudice,” to people’s experiences? Well, you say, of course it’s both! But which is the starting point? Which serves as the hermeneutical key to which? Which is the terra firma on which we can grapple with the other? Do we begin with our own strengths and weaknesses or do we begin with the Word of God?

It won’t do to say that the Word of God must be the Church’s starting point, then to proceed by seeking our point of departure in “the concrete situation of today’s families.” That is merely to give lip service to our Lord. In any case, the concrete situation of today’s families is no different than that of yesterday’s families in the most crucial respect. Ditto for the individual, whether or not he or she lives in anything recognizable as a family. Both stand before the Lord. That is what they most need to know and what the Church must always be prepared to tell them. How else will it know what is “positive” and what is “deficient” (§82) – indeed, what is good and what is evil, if we may use that word – in contemporary culture and habits?

4. The IL’s references to the Holy Family are mere tokenism.

It is asserted that the Holy Family “is a wondrous model” for the family (§58). But if the Holy Family is to be held up as a beacon in the dark, should there not be some analysis of what the Holy Family can teach us? There isn’t, nor is there a call for such, unless it be in the concluding prayer. But if indeed we are to pray, “Holy Family of Nazareth,

may the approaching Synod of Bishops

make us once more mindful

of the sacredness and inviolability of the family,

and its beauty in God’s plan,” then why is it that the IL itself turns a blind eye to the Holy Family? Why does it take no interest in the glaring contrast between the presuppositions of the society in which we live and those revealed by the Holy Family as fundamental to God’s purposes for humankind?

Why, for that matter, does it not propose in outline a theology of the body, of sex, or of the family itself? Why does it not use the appearance of the Holy Family to distinguish and to link the orders of creation and of redemption, or to expound the goods of marriage as the Church understands them? Is all that too much work, or is there some deeper reason for this failure?

5. The IL is far too reticent about sex.

A truly remarkable feature of the IL, given its professed interest in the concrete situation of families and individuals, is its reticence about sex. We live in a sex-saturated society, aided and abetted by the contraceptive mentality and by pervasive pornography. We also live in a time when even the basic categories of male and female are being abandoned. The gospel of marriage popular today is a gender-free “whosoever will” gospel.

Only fleeting references to these facts can be found in the IL. The attack on sexual dimorphism is noted (§8). Pornography is acknowledged as “particularly worrisome” (§33). Abortion puts in a cameo appearance at §141, as a “tragedy” to be countered with commitment to “the sacred and inviolable character of human life.” The contraceptive mentality is countered by several references to “openness to life” (§§54, 96, 102, 133, 136), though the word “contraception” is not to be found. That in itself is a remarkable feature, for the entire sexual revolution, with all its ideological and cultural and legal offspring, including widespread divorce, broken and fatherless families, religious ignorance, hopelessness, poverty, rape, abortion, gender confusion, drug abuse, etc., is built on ready access to contraception.

What kind of examination of “the concrete circumstances of our lives” is being undertaken here, if contraception can be referenced only obliquely, and the worldwide abortion industry only in passing? If recent trends in sexual behaviour and in the laws governing it don’t merit attention? If even the age-old problems of fornication and adultery make scarcely any appearance? The lack of frankness about sex and sexual practices is appallingly out of step with the cultural reality that the IL calls us to consider.

6. The IL compromises the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Now we might take the call to fix our gaze on Jesus and on the Holy Family to be a kind of shock therapy, shaking us loose from our sex-saturated culture so that we may learn how to acknowledge and engage it, confronting it with a call to conversion and salvation. But the drafters of the IL never mention just how startling Church teaching about the Holy Family is, or how truly countercultural it is. “A couple, even a married couple, who abstain from sex? An only son who chooses celibacy for the sake of his vocation? Do say!” But the IL doesn’t say.

The drafters of the IL are not interested in any kind of shock therapy. Quite the contrary. They are completely committed to “the law of gradualism” urged by Cardinal Kasper. That law – the law of the long, slow conversion through initiatives that progressively involve people in the life of the Church and move them towards its ideals (§63) – eschews anything shocking or demanding. It is always looking to split the difference, so to say, by encouraging a culture “capable of coherently expressing both faithfulness to the Gospel of Christ and [faithfulness] to the person of today” (§79).

But this only raises again the question of a starting point. For what is it that will mediate between the Christian gospel and the “person of today,” providing assurance that faithfulness to both is possible and showing what that faithfulness must mean? An answer of sorts has already been supplied: “The great values of marriage and the Christian family correspond to the search that characterises human existence, even in these times of individualism and hedonism” (§35). In other words, the search that characterises human existence mediates.

Here it is man’s innate capacity or instinct for God that is the true gospel. Hence we are not so much to preach Christ and him crucified, as to encourage people gently “in their hunger for God and their wish to feel fully part of the Church, also including those who have experienced failure or find themselves in a variety of situations” (§35). This may lead to various irregularities, of course, but it will all come out right in the end. Meanwhile, we must work with what lies to hand: “the determination of a couple,” for example, which “can be considered a condition for embarking on a journey of growth which can perhaps lead to a sacramental marriage” (§102). Well, perhaps it can, if the definition of marriage is altered, as it has been elsewhere, or if the restrictions around it are loosened, as the third part of the IL proposes.

7. The IL distorts Scripture and tradition in its attempt to dissolve indissolubility.

The Son of God, engaging the people of God within their own family culture, tightened rather than loosened the sixth commandment. The Church, building on Jesus’ exposition of Genesis and on the teaching of Paul, declared marriage not only permanent in principle but, between the baptised, actually indissoluble, given its sacramental character as witness to the union of Christ and the Church. The IL mentions this indissolubility in several places but, rather than facing squarely Jesus’ new rigour with respect to the sixth commandment, turns instead to his promise of a divine gift for those called to celibacy. Only it does not mention celibacy. It speaks instead of what it calls the “gift and task” of indissolubility (§41f.), which it redefines as “a personal response to the profound desire for mutual and enduring love.”

Indissolubility, in other words, is something subjective rather than something objective. It is reconceived, within the “Gospel of the Family,” as offering “an ideal in life which must take into account a sense of the times and the real difficulties in permanently maintaining commitments” (§42). Hence we are not surprised to find the IL speaking at §57f. of those who heroically model “the beauty of a marriage which is indissoluble and faithful forever,” as if to say to them, “Why, thank you very much for this rare and inspiring example in such difficult times!”

To be fair, Church teaching on indissolubility, not as an ideal but as an objective norm, is acknowledged at §99 and §120, but it is immediately relativized by appeals to the law of gradualism and “the art of accompaniment.” The document’s handling of Scripture and tradition is not merely unsystematic, but tendentious in the extreme. It has to be, in order to convert indissolubility from a fact to a task.

8. The IL dissolves instead the sacrament of marriage.

The IL recommends that the Church look again at “the connection between marriage, Baptism and the other sacraments” (§94). This is certainly the right thing to do, but it is done in just the wrong way. By championing the cause of those who wish to loosen “the present discipline” by “giving the divorced and remarried access to the Sacraments of Penance and the Eucharist” (§122), the IL overlooks the fact that Baptism already gives access to Penance, and Penance (in the case of grave sin) to the Eucharist. The real question, never posed and indeed carefully avoided, is whether the penance for adultery must include ceasing the adulterous activity of a sexual union with someone other than the baptised person one initially married.

If it must, then there is no real issue here, though of course there are still many prudential pastoral judgments to be made inside and outside the confessional. If it need not, then there is no distinction to be made between marriages made and broken outside the bonds of Baptism and marriages made and broken inside. That is, there is no longer a difference between marriage in the order of creation and marriage in the order of redemption. The Protestant reformers were right after all: there is no sacrament of marriage.

9. The IL misconstrues spiritual communion.

The IL also recommends clarification of “the distinctive features of the two forms” of spiritual communion (§124), one of which permits full communion and one of which, inexplicably, does not. But there are not two forms, only two quite different circumstances, one of which has a limiting effect the IL does not wish to acknowledge.

The 1983 Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on Certain Questions Concerning the Minister of the Eucharist speaks of the spiritual communion of those are who are unable to be present at the Eucharist by reason of persecution. These “live in communion with the whole Church…; they are intimately and really united to her and therefore receive the fruits of the sacrament.” The 1994 CDF document, Concerning the Reception of Holy Communion by Divorced and Remarried Members of the Faithful, addresses itself to those who are engaged in a penitential process, by reason of sin. In the former case, spiritual communion is a substitute for full communion because of bodily separation, and all the fruits of the sacrament appertain. In the latter case, spiritual communion is a substitute for full communion because, in bodily proximity, there remains a spiritual distance – the distance of the penitent who has not yet taken all the necessary steps to bring his life into conformity with dominical teaching. In such a case, it cannot be said without qualification that all the fruits of the sacrament appertain. So in both cases full communion is hoped for, but the path to that communion is not the same in each.

The 1983 Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on Certain Questions Concerning the Minister of the Eucharist speaks of the spiritual communion of those are who are unable to be present at the Eucharist by reason of persecution. These “live in communion with the whole Church…; they are intimately and really united to her and therefore receive the fruits of the sacrament.” The 1994 CDF document, Concerning the Reception of Holy Communion by Divorced and Remarried Members of the Faithful, addresses itself to those who are engaged in a penitential process, by reason of sin. In the former case, spiritual communion is a substitute for full communion because of bodily separation, and all the fruits of the sacrament appertain. In the latter case, spiritual communion is a substitute for full communion because, in bodily proximity, there remains a spiritual distance – the distance of the penitent who has not yet taken all the necessary steps to bring his life into conformity with dominical teaching. In such a case, it cannot be said without qualification that all the fruits of the sacrament appertain. So in both cases full communion is hoped for, but the path to that communion is not the same in each.

When the IL points out that “spiritual communion, which presupposes conversion and the state of grace, is connected to sacramental communion” (§125), it conflates these two very different circumstances in hopes of getting round the requirement that people in adulterous relationships either break them off or convert them into non-adulterous relationships. It ignores the fact that the sacrament of penance is incomplete and that a state of grace cannot be presupposed. It suggests that, if spiritual communion is encouraged, sacramental communion – now, not later – is a simple matter of justice. Which is entirely contrary to every existing magisterial intervention on the subject, including what it bizarrely calls (§121) the “recommendations” of Familiaris Consortio §84, though these are reiterated and still further entrenched in the Declaration Concerning the Admission to Holy Communion of the Faithful who are Divorced and Remarried of the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts (2000).

10. The IL lacks all sense of proportion.

Why does the question of the admission to Holy Communion of the divorced and civilly remarried emerge as so prominent a question in the IL? Why are we reminded, just here, that “the necessity for courageous pastoral choices was particularly evident at the Synod” (§106)? In the face of grinding poverty and brutal terrorism and state coercion and a degree of moral confusion that defies even the very concept of the family, it seems rather odd to fix on this particular proposal. In societies in which the Catholic vision of sex, marriage, and the family has become all but incomprehensible to the general populace, and indeed to many Catholics, through a major breakdown of the Church’s mission to convert and to catechise, why is communion for the divorced and remarried the one thing with which we must have the courage to deal?

It is implied that admitting the divorced and civilly remarried to Holy Communion is a token, not only of the Church’s justice, but also and more especially of its mercy or tenderheartedness. But how is encouraging penitents to stop short of the goal – for such is the real effect of this proposal – tenderhearted? And will it not turn what the Holy Father called “the great river of mercy” (Misericordiae Vultus §25) into a conduit for counterfeits of every kind? Why not add, for example, the blessing of same-sex unions, since they too are built on “the determination of a couple”? One suspects that talk of mercy is being made to serve some other purpose here, as is the focus on admission to Holy Communion of the civilly remarried.

11. The IL belongs to the Humanae Vitae rebellion.

We do not have to look far to discover that purpose. At §134 the IL makes the very odd remark that “some see a need to continue to make known the documents of the Church’s Magisterium which promote the culture of life in the face of the increasingly widespread culture of death.” Others, we must assume, would be happy to bury them, and this the IL does not discourage. Indeed, it sets up the very same dialectic used in the historic attempt to dispose of Humanae Vitae, a dialectic explicitly repudiated in Veritatis Splendor and other magisterial documents. In this dialectic, claims about objective moral norms are balanced by the discernment of conscience, such that each serves to limit the other. As the IL puts it: “A person’s over-emphasising the subjective aspect runs the risk of easily making selfish choices. An over-emphasis on the other [objective aspect] results in seeing the moral norm as an insupportable burden and unresponsive to a person’s needs and resources” (§137). It is not too much to say that, if this particular passage is allowed to stand, the entire Catholic moral tradition must fall.

Let us not remain at too abstract a level, however. We should admit that the Humanae Vitae rebellion was and is a rebellion over sex itself; that is, over marriage understood in 20th-century Protestant fashion as more unitive than procreative and indeed as a licence (increasingly regarded as unnecessary) for carnal pleasure. That base view of sex and marriage demands the embrace of contraception that Humanae Vitae, like Casti Connubii, forbids. Truth be told, it also demands the embrace of same-sex marriage, which many western Catholics now champion. What is the “insupportable burden”? It is the burden of continence or chastity; the burden, as Elizabeth Anscombe puts it, of virtue in sex.

Here, I dare say, we have the main reason for all the machinations described above, from the refusal to mention contraception through to the mishandling of Christ’s teaching and on to the proposal itself – the proposal that the burden of abstaining from sex not be imposed on those who are repenting of adulterous civil marriages. The simple fact of the matter is that “the person of today” refuses to accept this burden. And why should he, if he will not accept the burden of continence even in a faithful sacramental marriage?

12. The IL is deeply implicated in the crisis of faith.

The final flaw of the IL is that it is deeply implicated in the very crisis of faith of which it speaks, and in a rebellion against magisterial authority that it is careful to deny. In point of fact, what it angles towards at every possible opportunity is the overturning – now at last in principle, as already in practice – of Humanae Vitae and its sister documents. What better place to do it, what more satisfying venue, than a Synod devoted to the family? And under what better rubric than the “Gospel of the Family”?

I have already said that, if this rebellion succeeds, magisterial authority falls. So does the Catholic vision of man – which, as Anscombe pointed out when Humanae Vitae appeared, was never that of “the person of today.” The same may be said of the Catholic vision of the Church itself, and of the sacraments. Which leads to the question, how can this rebellion have got so far?

We should not be too quick to vilify the usual suspects. It has got this far because too many bishops and priests who lament this great crisis of faith and of obedience have lacked the courage to respond to it. Some of them are making a good deal of noise, even now, about protecting marriage, protecting the integrity of magisterial teaching and authority, protecting people too. Yet they themselves have failed to acknowledge what is entirely obvious: The Church cannot withhold Holy Communion for one grave sin, viz., an adulterous civil marriage, while not withholding it for another, viz., the recalcitrant use of contraceptives. That is an entirely unsustainable position, and everyone knows it. Bishops and priests who have abandoned all sacramental discipline in the matter of contraception to the private judgments of “the faithful” have already capitulated to the subjectivism that powers this rebellion.

We do indeed need courageous pastoral choices. There is an “urgent need to embark on a new pastoral course.” But it is false and cowardly to say that the course must be “based on the present reality of weaknesses within the family.“ That is not an assertion of the gospel of the family, but a denial of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. No! The new course must be based on repentance for past and present unfaithfulness, and the promise of renewed grace. It must be based on a deeper fidelity to Scripture and tradition. It must be based on a new willingness to bear the cross, the sign of contradiction. For that is where the divine mercy has been invested.

IMPORTANT VOICES

…for the Synod and the Church to hear

Anthony Fisher, OP, is the Archbishop of Sydney, Australia, having previously served as auxiliary of that archdiocese and Bishop of Parramatta. After working as an attorney he entered the Dominicans and, following ordination to the priesthood, earned a doctorate in bioethics from Oxford with a dissertation on “Justice in the Allocation of Healthcare.” Pope Francis appointed him a member of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 2015. Letters from the Synod asked him to reflect on the crisis of marriage and the family and his hopes for the Synod through the prism of his pastoral experience – as we’ve asked other bishops and lay experts whose answers will appear in this space in the days and weeks to come. XR2

1. In your pastoral experience in Parramatta and Sydney, what are some of the particular ways the contemporary crisis of marriage and the family — the contemporary crisis of chastity, really — have presented themselves to you?

Over the last few decades there have been some very real advances in appreciation of romance and intimacy in marriage, in respect for the dignity of women and children, in the sharing of lives and responsibilities between spouses, and in the theology and pastoral care of marriages. Yet even as our understanding of relationships has been enriched in these ways, modernity has found itself in a mess about marriage. When I was a child growing up in Australia most people got married and stayed married; in contemporary Australia (as in many other countries today) most people of marriageable age are not married and many who try fail to persevere. Many now live singly or in a series of temporary relationships. Eventually one of these relationships may settle into being a sort of ‘de facto’ marriage. At some point, perhaps when a couple are thinking of having children, they may decide to solemnise it – interestingly, this means that deep down most people know marriage has got something to do with children. But after years of try-before-you-buy and habitual non-commitment, many find they cannot sustain actual marriages once entered. Some try again – and fail again. Many eschew child-bearing altogether; some want children but in limited numbers, later in life, after achieving other goals. Many children now grow up without ever experiencing the love and care of a mother and father committed to each other and to them over the long haul; that makes them in turn less likely to aspire to and achieve stable marriage themselves. We all know and love people who have suffered from family breakdown; every serious social scientist and thoughtful economist understands the costs of this. Theories abound about the whys and wherefores of all this, but the what is undeniable: never before in history have we been so unsuccessful at marrying.

If we are not as good at entering and sustaining marriages as we were in the past, it is surely significantly because we are so confused about the defining dimensions of marriage. It’s hard to play football well without knowing the objects and rules! The 1960s sexual revolution, fuelled by the Pill, meant the exclusivity and for-children-ness of marriage and marital acts became elective in many people’s minds. The 1970s advent of no fault divorce meant the for-life-ness of marriage also became an optional extra. In the ’80s privatised ‘de facto marriage’ meant the for-society-ness of marriage became discretionary, and the 1990s push for out-of-church weddings meant the for-God-ness was also. Most recently, under the slick slogan of ‘marriage equality’, the for-man-and-wife-ness has also been challenged; and next, on the near horizon, the for-two-people-ness will likely go.

At its base I think this is modernity experiencing a profound crisis in loving: put baldly, we have forgotten how to love. That sounds strange in a culture supersaturated with love longs and other love talk. But as I’ve sometimes put it: we have plenty of the romanticised, self-pleasing, heart-shaped, Valentine’s Day kind of loving: but what we most need right now is self-giving, cross-shaped, Easter Day kind of loving. Easter loving takes fidelity and commitment, self-sacrifice, a willingness to compromise our will for the sake of the other, endless forgiving – and chastity, understood as the virtue that integrates sexuality with the rest of personality and into our whole vocation. Marriage is about so much more than a promise to try to have certain feelings towards someone for as long as it lasts: it is a comprehensive spiritual, psychological, sexual union of a man and woman; it changes a man and a woman into “husband” and “wife”; and in doing what husbands and wives do allows the possibility of children. But modernity says “no” or at best an ambivalent “maybe” to all that.

A culture that is so mixed up about love and marriage won’t be doing a very good job at “marriage preparation”. Selling people on happiness through individualistic self-regard, instant gratification, gadget possession, career before children, pornography addiction, hook-ups and other disordered sex is not helping them marry; indeed it is inoculating them against marriage and family. Vaccination works by giving people small doses of dead or nearly dead versions of the real thing, just enough to build up resistance: by giving people doses of quasi-marriage, of marriage lite, of marriage without the for-life-ness, for-man-and-wife-ness, for-children-ness, for-God-ness, for-society-ness, modernity exposes them to what will make them immune to entering and succeeding in real marriages.

2) What pastoral strategies and initiatives have you found most effective in dealing with these challenges?

A genuinely pastoral approach to this contemporary crisis is not one that gives people more marriage-lite, more of the vaccinating half-dead virus. It is one that helps people recover an understanding of God’s plan for marriage, recover an appreciation of its beauty, recover the kind of character required to achieve something so good and so hard.

I have a priest friend who is a very popular wedding celebrant. As you’d expect, many of the couples who approach him give the same address on their pre-nuptial inquiry form. He is lovely with them, commending their romance and idealism, asking them about marriages they have known and their own hopes. He gently but clearly teaches them the Christian hopes for marriage. He appeals to their innate goodness, indeed to their heroism, and so presents the challenge to them (perhaps especially to the groom): do you love (her) enough to put the marriage before your own gratification? Can you make it to the wedding night without having sex?! My friend reports that some of them take up the challenge and make it; they report an improved relationship as a result.

My thought here is that effective pastoral strategies are never ones that acquiesce in the very problem they are supposed to be addressing. The more confused a society is about marriage the more determined we must be to present the truth about marriage and the sort of behaviour that leads to good marriages with clarity, passion, persuasion. Rather than old men hectoring people as if sexuality and marriage were all about avoiding what is forbidden, we can reveal the nature of the spouses and the moral law that serves their happiness in ways perhaps surprising in our culture but ultimately alluring. One thing I’ve been concerned to work at is that our seminarians, priests, and school teachers know about the rich theology of the body, and of marriage and family, that our tradition offers, and are equipped to present it in ways that people find credible and encouraging.

So I’ve been a strong advocate of the John Paul II Institute for Studies of Marriage and the Family, the several campuses of which around the world offer centers of excellence in this sort of reflection, research and teaching. In three dioceses in which I’ve worked (Melbourne, Sydney, and Parramatta) I established Life, Marriage and Family Centres which help mediate that high level thinking to the grassroots of our parishes and pastoral programmes.

3) What are your hopes for the Synod? How can its work have a positive effect on your own pastoral work?

Hopefully the Synod will be remembered for presenting the beauty of Christian teaching on sexuality, marriage, and family, and positive pastoral strategies for recovering an appreciation for them in our culture and among our faithful; for supporting people in embracing and living marriage well; and for recommending to all things that have worked on the ground for some. The Synod must start with the positives, with the vision splendid about marriage, rather than focusing all its attention on the headline-grabbers such as same-sex ‘marriage’ and Holy Communion for the divorced and remarried. We must not let the New York Times dictate the terms to a Synod of Bishops of the Catholic Church.

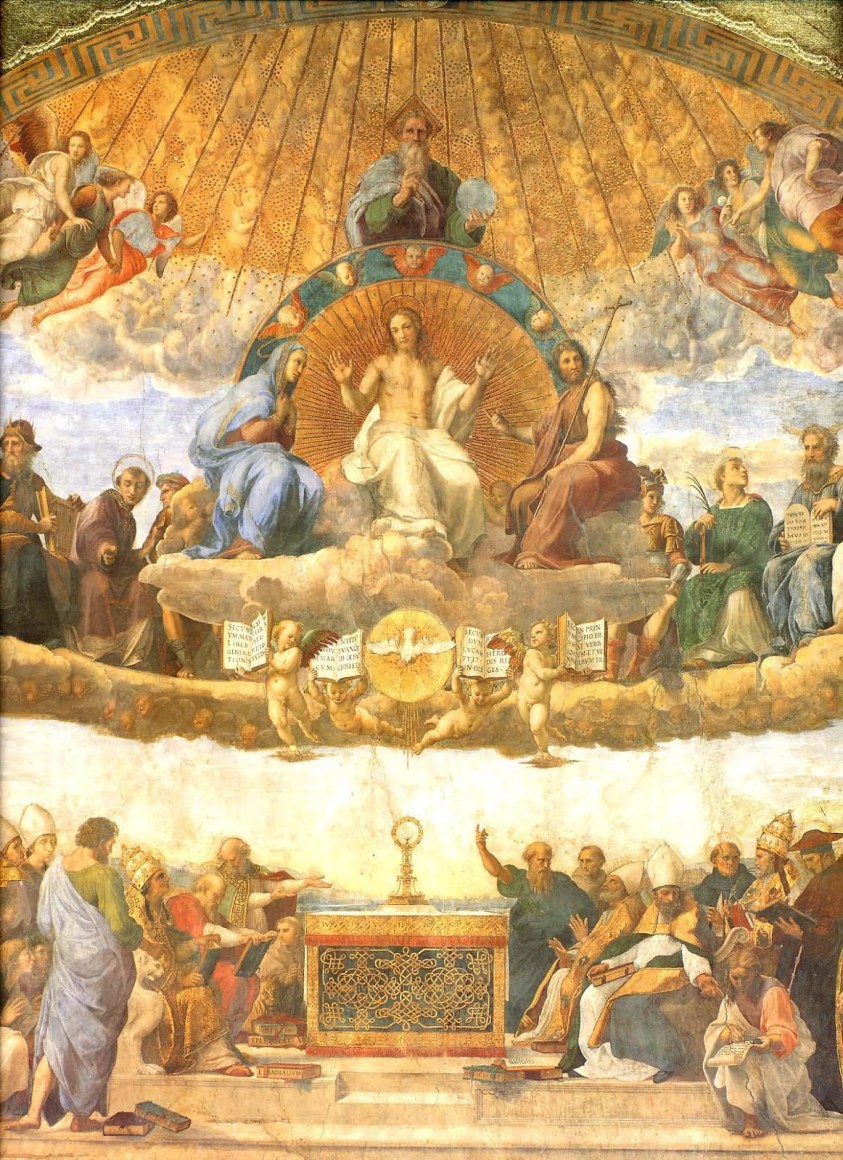

With a rich, positive, theological framework in mind, the Synod will be able to offer the Church in various localities ideas on assisting would-be married couples and already-married couples to live out their vocations and create “domestic churches” in which their children can grow in Christian holiness. Having addressed the central case, the Synod can then reach out to those on the peripheries of family life or in irregular situations with various ideas on how they too can be more closely united to Christ. In the end a Catholic Synod on marriage – as opposed to a secular, academic talkfest – must start and finish with “the Marriage of the Lamb”, the marriage of Christ to his bride the Church and how we might be conformed to that marriage; must start and finish with “the Family of God”, our adoption by Word and Sacrament, by Grace and Virtue, into the family of God the Father and the communion of saints. Start there and only then reflect on contemporary challenges, and many creative and effective pastoral strategies will follow.

Related: The Synod’s script is

atrocious